Pallas

The beauty of shape

In 1955 Citroën abandoned Traction Avant, launched in 1933, and created the revolutionary DS automobile with hydropneumatic suspension. ID followed soon after, a far more popular model, and then the deluxe Pallas version.

Pallas is also one of the many nicknames for the goddess Athena but according to a later legend, it is also the name of one of Triton’s daughters, Athena’s girlhood friend, accidentally killed while they were playing. To pay her homage and to keep her memory alive it appears that Athena added her friend’s name to her own and moulded the Palladium, a statue that is said to have magical properties. Mythology offers yet another variation: Pallas was one of the Giants, he himself father of Athena who wanted to rape his own daughter but she killed and skinned him and used his skin to make the legendary cuirass.

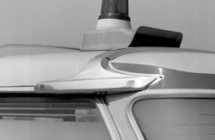

But our purpose is not to talk about Olympus but to present Cesare Di Liborio’s photographic work that has immortalised the beautiful shapes of the car that bears the same name. This car is astoundingly modern with incomparably elegant lines and perfection in comfort. Everyone who has ever tried it agrees, before they finally, and all too soon, have to let it go, that nothing better has ever been created.

All that is left is a feeling of nostalgia. Volumes and a few specimens of the vehicle remain as homage to its excellency that Cesare Di Liborio manages to render so very well. But he had the idea of separating the elements and fit them in where they can still exert their power of seduction to the full. Since Pallas provokes sensations of beauty and subtle eroticism, highly intriguing, at times functional at times “sensual”, it maintains its identity down the years which would normally have rendered it obsolete. A feeling of “interior disturbance” (perturbation) resulting precisely from this phenomenon in a world where everything is normally hurled into the whirlpool of the past and at a constantly quickening pace.

Cesare Di Liborio perfectly understood this permanency which he associated to the sculpture, to the volume, to the shape. In everyday language the shape determines the state in which we perceive the substance of a certain object and which comes from the construction and arrangement of the parts. It is something solid and palpable. The figure assumes a more abstract meaning which is preferable for visible things, it is the superficial shape of things. The sculpture creates the shapes, the artist paints the figures, the photographer combines shapes and figures.

But Cesare Di Liborio does not forget man in his meticulous and superb account of Pallas. He remembers that the creative work of a designer for the bodywork and the work of an engineer for the mechanical parts are at the roots. And this is how his work transforms into appreciation for configuration and shape which goes to say the example par excellence of industrial beauty, the automobile that was quite rightly called Pallas.

Charles-Henri Favrod

Contattaci